Managing Logging in a Multi-Module Android Application

Table of Contents

In this article I will show you how we adapted our logging strategy to a massively grown project structure. In the first part I will go through the issues we had with the current setup and in the second part, what steps we took to improve them.

Part I #

Issue #1: Many Modules & Libraries #

Our module layout consists of a growing number of about 15 Android modules and 4 Java modules. Additionally we have around 5 in-house libraries/dependencies we use and of course countless third-party libraries. A chaotic mixture of LogCat, SLF4J and a couple of home-brew loggers are used without any real centralized configuration.

Issue #2: Using Custom Loggers #

Apart from LogCat we used a very basic custom facade called Flog. It would log the output to an internal file in addition to the console for better crash reports. There were clear rules when to use Flog and when Log but at that time we had 4 modules and different people working in the project. Over time, it was forgotten to use Flog and often times important log info was lost while finding specific bugs.

Issue #3: Inflexible SLF4J Android Binding #

Most Java projects we depend on use the common logging facade SLF4J. There are multiple bindings for Android’s LogCat but they all share the same behavior: they respect the isLoggable(tag,level) check. This seems like the correct way of checking whether a message should be logged or not, but unfortunately it does not make much sense. The isLoggable method expects a tag and asks if a certain level might be logged, but this means every class that uses a logger must be defined (not even talking about how to know all those names)

Issue #4: Logging in Production #

Ideally we want no log output in production. For one, we don’t want to reveal private or confidential data of our users or give away too much how the app works. Additionally, logging incurs, even if only small, a performance penalty we don’t want to accept in a production build were we want to show the user how amazingly fast our service is.

The current setup, which is just based on Proguard rules removing (part of) the logging statements, is not very stable. Changes in the config might go unnoticed and will break the protection. It so happened that a 3rd party lib added -dontoptimze to the Proguard configuration in its consumerProguardFile which disables code removal.

Issue #5: Guidelines when to Log at what Level #

Like many projects, ours started with only 2 developers and was in rapid prototyping mode. There were no guidelines or discussions about logging, everyone assumed to be on the same boat. 3 years, 10k commits and 15 developers later, this turned out not be true. It wasn’t terrible but the decision when to use either info, debug or verbose seemed often times random.

Part II #

In this second part I will show step-by-step how we improved on the points detailed above.

Step 1: Choosing the Logger that’s right for you #

After analyzing our current issues we can deduce the following requirements for our new main logger:

- Centralized, stable and easy configuration

- Not too different from the “Android way” of logging to make it easy for developers to adapt and to increase acceptance

- Migration should be as easy as possible

- It should be well-known and accepted in the community, in the sense that if a new team member joins there’s a chance that he or she worked with this framework.

- Above all: it just should be easy and simple — in the end, it’s just logging.

The first contender was SLF4J, the Java logging facade. Unfortunately this checked only one of our requirements: well-known and accepted. SLF4J allows centralized configuration, but it is not easy. If you use a published binder library there’s usually no way to change any behavior — if you want full control you have to implement it yourself (I think this requires 5 classes to implement, most of the stubs for Android). The gluing of the code works like in the old Java days: the library searches through reflection for a class that implements LoggerFactory in the classpath. The binding therefore works implicitly and seems like magic if you don’t know what it’s doing. The whole SLF4J framework offers a huge amount of features which most are irrelevant in an environment where everything runs on the same device. Finally, it has very different in handling compared to android.util.Log.

Our next contender was Jake Wharton’s Timber logger. It has easy centralized configuration: you just implement a so-called logging Tree and plant() it in debug builds. If no Tree is planted, logging is a no-op. It is very similar to the API provided by android.util.Log with the additional convenience that no TAG has to be provided (Timber figures this out itself, and it works quite well, even in e.g. anonymous classes; I can however not comment on any performance implications this might have). With over 5k stars on GitHub and just by the fact that it’s created by Android’s most popular developer Mr. Wharton ❤ himself, it is probably sure to say that most mid-level Android developers have at least heard of this library by now. Looking at the source code, this is just a single class with a very simple interface to implement your own behavior. Timber seems to check all the boxes.

Timber additionally has also 2 very handy features: For one it supports logging without the need for string concatenation (SLF4J has a similar feature). So instead of

Log._v_(_TAG_, "this a simple Log.v message with " + stringValue);

you write

Timber._v_("this a simple Timber.v message with %s", stringValue);

The advantage is that this will save you 3 allocations in the memory constraint world of Android, as explained by the android.util.Log‘s Javadoc

Don’t forget that when you make a call like ‘Log.v(TAG, “index=” + i);’ that when you’re building the string to pass into Log.d, the compiler uses a StringBuilder and at least three allocations occur: the StringBuilder itself, the buffer, and the String object. (…) even more pressure on the gc. (…) you might be doing significant work and incurring significant overhead.

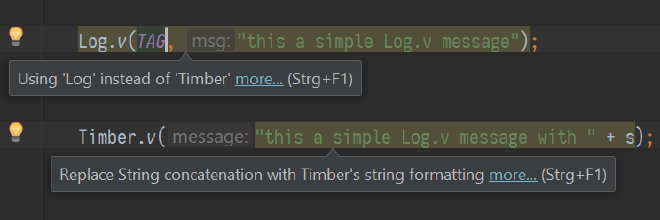

And two, it supports a lot of very convenient lint checks. For example, it warns you if you, like explained above, use string concatenation instead of string formatting or just that the android logger is used. Most of the rules have quick-fix options making migration a charm:

The main drawback: Timber does not work with plain Java code since it is published as an AAR. I wish it would have an interface Java library and an Android implementation library which would also make handling dependencies with different versions of Timber easier.

For Java modules we kept SLF4J, since most third party Java libraries already use it and it is basically the standard way of logging in the plain old Java world. All the SLF4J calls will be routed through Timber with the slf4j-timber binding I implemented (I later found out that there is already an implementation around 🤦).

Conclusion: Timber for Android, SLF4J for Java with Timber binding

Step 2: Migrating our custom Logger #

This section might not apply to many projects, but it shows how easy it was to add custom behavior transparently to the new concept.

As mentioned above, one of our requirements is that we log important messages to an internal rolling log file which will be appended when our internal error tracker sends a crash report. Some of our features heavily suffer from fragmentation of Android devices, therefore this debugging info was often vital in finding some of the more obscure bugs. With Timber a new Tree was implemented and “planted” parallel to the DebugTree:

public void onCreate() {

Timber._plant_(new Timber.DebugTree());

Timber._plant_(new TimberFileTree());

}

The internal rule-set defines that Info, Warn, Error and WTF log levels will additionally be logged to the internal file. This makes this feature practically transparent for developers nobody has to decide when to use which logger since the usual Timber.i() will already do correct thing.

Conclusion: if required, implement your own Tree

Step 3: Disabling Logging in Production #

Logging in production is bad. It exposes possible confidential information and slows the application. Also

(…) every time you log in production, a puppy dies. — Jake Wharton

Since we now have a centralized logging config, we should make use of it. In our application’s onCreate() we plant the DebugTree only in a debug build:

public void onCreate() {

...

if (BuildConfig._DEBUG_) {

Timber._plant_(new Timber.DebugTree());

}

Timber._plant_(TimberFileLogTree._get_());

}

Apart from legacy or third party libraries your app will now be silent in production. To go a step further, and to prevent evil hackers from reading your log messages (making it easier to understand the code), we let Proguard remove them for us. First is Timber itself:

**\-assumenosideeffects** class timber.log.Timber {

public static \*\*\* v(...);

public static \*\*\* d(...);

}

Then SLF4J logging:

**\-assumenosideeffects** class org.slf4j.Logger {

public \*\*\* trace(...);

public \*\*\* debug(...);

}

And finally all the legacy Android logging:

**\-assumenosideeffects** class android.util.Log {

public static \*\*\* v(...);

public static \*\*\* d(...);

public static \*\*\* i(...);

public static \*\*\* w(...);

}

Please note the following:

- We only remove debug and verbose logs since our internal file logger logs everything above that. This might not make sense in other projects, and you may safely remove all levels.

- We remove practically everything from Android’s logging since this is basically just for legacy and third party libraries (which we don’t trust to be sensible when it comes to logging); Timber uses Log.println() so it won’t be affected by this

- This will only work when Proguard’s optimize is enabled. Read more here.

- If an exception should be logged, that shouldn’t land in production builds just use debug or verbose like Timber.v(exception, “”)

Conclusion: a simple if and some Proguard rules will take care of that

Step 4: Migration #

Here’s the annoying part: manually migration Log.* to Timber.*. Lint’s quick-fix option in Android Studio will help you, but it’s going to be a chore. In our case, we immediately migrated some of the core modules and will adapt on-the-fly when touching older classes.

During migration the following two issues popped up often:

- Leaving the TAG in the method signature like Timber.v(TAG, msg) which will break the log message, since the msg is now expected to be a placeholder for the first parameter, in this case TAG. A full-text search in your project for e.g. Timber.v(TAG will reveal these issues.

- Since Timber uses varargs as the last parameter, the Throwable parameter moved to the first place. Compare for instance Log.w(TAG, “msg”, exception) vs Timber.w(exception, “msg”)

If there are any Java modules using other logging frameworks (or something home-brew), switch to SLF4J. If you never used it, here is a quick start. First add the dependency to the slf4j-api:

implementation 'org.slf4j:slf4j-api:1.7.25'

then you can log with

private final Logger logger = LoggerFactory._getLogger_(MyClass.class.getSimpleName());

...

logger.debug("my message");

in your main module (usually the app module), add the binder implementation to your dependencies

implementation 'at.favre.lib:slf4j-timber:1.0.0'

Conclusion: it’s going to be painful, just mind to caveats.

Step 5: Logging Level Guideline #

This section is quite subjective and might or might not work with your project or team, so your mileage may vary.

- Verbose/Trace: Either very chatty or only relevant for very specific edge cases. This level may include sensitive or confidential data if it helps debugging. Example: view position when dragging.

- Debug: The baseline, when in doubt use this level. It may contain sensitive data but probably should not include confidential data. Example: http network log

- Info: For very important and high level logs. This must not include any sensitive data. If in doubt, think if the message would be a problem if it would be accidentally logged in production. Example: onCreate of an Activity signalize start of a new screen.

- Warn: Issues which might not prohibit normal use, but to be aware of. Example: network timeout in background request.

- Error: For exceptions or fatal states. In doubt, log the exception. Example: any catch bock.

- WTF: Usually avoid; only useful if in the error recovery something happens or something that should basically never happen.

A Note for Library Developers #

Enabling logging is the responsibility of the main module (i.e. the app). Do not ever directly use Log.*; or worse, any home-brew logging faced. Either use SLF4J without binding or Timber without a planted Tree. With this configuration the library user has the full control over logging of all the dependencies/modules. Just add a section in your GitHub’s readme.md how to configure the logging framework.

Conclusion #

We centralized our logging with Timber for Android modules and SLF4J with Timber binding for Java modules. We adapted our custom logger by implementing a custom Tree. With Proguard and a simple if we can easily remove all logs from the release builds. Timber’s own Lint quick-fixes will help migration a bit of which we do most on-demand when touching old code. By setting a clear guideline it should be clear when to use either log-level.